Three years ago, during my undergraduate studies in Computer Science at ESPOL, I had the opportunity to participate in research that completely changed my perspective on the applications of computational science. What started as an academic project became a scientific publication that demonstrated the power of applying computer science algorithms to real-world problems in materials science.

This experience was both exciting and challenging - it marked my first deep dive into applying computational science to interdisciplinary fields, showing me how algorithms I learned in class could have profound impacts beyond traditional software development.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

- The Challenge: When Computer Science Meets Materials Science

- What is Geometric Tortuosity?

- The Eureka Moment: A-Star as a Solution

- Implementation: Challenges and Breakthroughs

- Results That Exceeded Expectations

- Validation: Hydraulic vs Geometric Tortuosity

- Reflections: The Impact of Interdisciplinary Research

- Real-World Applications

- Open Source and Reproducibility

- Impact and Publication

- Lessons for Future Researchers

- Looking to the Future

- The Personal Journey: From Code to Science

- Conclusion: When Passion Meets Purpose

The Challenge: When Computer Science Meets Materials Science

Throughout my studies, I was always fascinated by the idea that the algorithms we learned in class could have applications beyond traditional software development. This passion led me to collaborate with Dr. Mayken Espinoza-Andaluz and his team at the Center for Renewable and Alternative Energy at ESPOL.

The problem we faced was complex: How to efficiently calculate geometric tortuosity in two-dimensional porous media? For someone without training in materials science, this sounded like science fiction, but I soon discovered it was a real problem with important applications in fuel cells, filters, and biomedical materials.

What is Geometric Tortuosity?

Geometric tortuosity is an intrinsic property that characterizes the morphology of porous materials. Imagine you need to find the most efficient path through a maze full of obstacles: that path complexity is similar to what tortuosity measures.

Mathematically, it’s defined as:

τgeometric = Lg / L0Where:

Lgis the average length of effective routesL0is the length of the shortest path (straight line)

This metric is crucial for understanding how gases, liquids flow or how chemical species diffuse through porous materials like diffusion layers in fuel cells.

The Eureka Moment: A-Star as a Solution

During the first weeks of the project, I found myself studying different approaches to calculate these effective routes. Traditional methods included algorithms like Dijkstra, direct shortest-path search, and skeleton-based methods. That’s when it occurred to me: why not use A-Star?

A-Star is a pathfinding algorithm widely known in video games and robotics. Its beauty lies in combining the guarantee of finding the optimal path (like Dijkstra) with the efficiency of a directed heuristic search.

Why A-Star?

- Computational efficiency: Significantly reduces search time compared to exhaustive methods

- Flexibility: Can move in 8 directions (cardinal and diagonal)

- Optimization: Finds the shortest path while avoiding solid obstacles

Implementation: Challenges and Breakthroughs

Digital Porous Media Generation

We used Python’s PoreSpy library to generate synthetic porous media with different porosity levels (0.5 to 0.9). Each medium was represented as a 100×100 pixel binary matrix:

0= void space (where fluid can pass)1= solid material (obstacle)

The Adapted A-Star Algorithm

The traditional A-Star formula we implemented was:

f(n) = g(x,y) + h(x,y)Where:

f(n)is the total node weightg(x,y)is the actual cost from the initial nodeh(x,y)is the heuristic estimation (Euclidean distance)

Conceptual Code

def calculate_geometric_tortuosity(porous_matrix):

start_nodes = find_inlet_nodes(porous_matrix)

end_nodes = find_outlet_nodes(porous_matrix)

total_paths = []

for start in start_nodes:

for end in end_nodes:

path = a_star_pathfinding(porous_matrix, start, end)

if path:

path_length = calculate_euclidean_length(path)

total_paths.append(path_length)

avg_path_length = np.mean([min(paths) for paths in group_by_start(total_paths)])

straight_length = matrix_width # L0

return avg_path_length / straight_lengthResults That Exceeded Expectations

Empirical Correlations

After analyzing 540 samples (60 for each porosity level), we developed three empirical correlations to predict tortuosity:

- Power (the best):

τ = 9.112×10⁻² × φ⁻²·¹⁵⁵ + 0.9093 - Exponential:

τ = 3.524 × e⁻⁴·⁶⁶⁴×φ + 0.9703 - Polynomial:

τ = 1.142φ² - 2.328φ + 2.187

The power correlation achieved a coefficient of determination of 99.7%, meaning our model predicts tortuosity with extraordinary precision.

Comparison with Other Methods

| Algorithm | Tortuosity τ | Relative Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A-Star (Ours) | 1.2747 | - |

| Pore Centroid | 1.3831 | 8.503 |

| Skeleton (PoreSpy) | 1.4109 | 10.685 |

| Dijkstra | 1.3213 | 3.655 |

Validation: Hydraulic vs Geometric Tortuosity

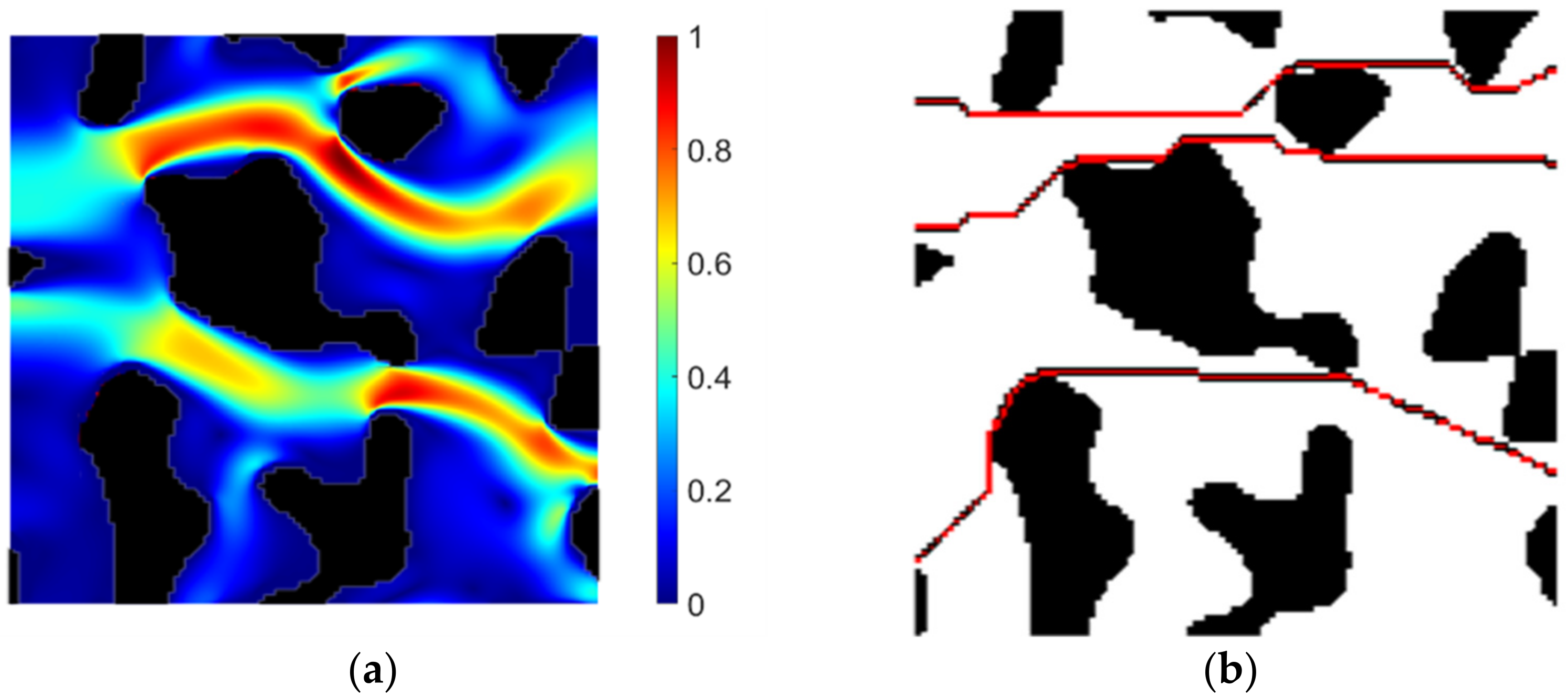

To validate our results, we compared geometric tortuosity (calculated with A-Star) with hydraulic tortuosity (calculated using the Lattice Boltzmann method). The results showed:

- Hydraulic tortuosity: 1.1768

- Geometric tortuosity: 1.1342

- Difference: Only 3.7%

This small difference confirms the validity of our approach and aligns with theory establishing that geometric tortuosity is always lower than hydraulic tortuosity.

Reflections: The Impact of Interdisciplinary Research

What I Learned

This experience taught me several valuable lessons:

- Algorithms have life beyond code: An algorithm designed for video games can solve problems in materials science

- The importance of validation: It’s not enough that it works; it must be compared and validated with established methods

- Statistics is your friend: Analyzing 540 samples gave us the statistical confidence necessary for our conclusions

The Emotional Side of Research

I vividly remember the moment when the first results arrived and the correlations began to take shape. Seeing how an algorithm I had implemented was generating data that could contribute to designing better fuel cells or biomedical materials was absolutely exciting.

There were also challenging moments. Debugging why certain porous media didn’t generate valid paths, optimizing performance to process hundreds of samples, and understanding materials science literature as a computer science student were challenges that made me grow as a researcher.

The transition from pure theoretical computer science to applied interdisciplinary research was both thrilling and daunting. It required me to learn an entirely new vocabulary, understand physical phenomena, and bridge the gap between algorithmic thinking and materials engineering.

Real-World Applications

The results of this research have direct applications in:

1. Fuel Cells

- Gas Diffusion Layers (porosity 0.55-0.80)

- Catalyst Layers (porosity 0.40-0.60)

2. Biomedical Materials

- Bio-based Porous Materials (porosity 0.70-0.95)

- Scaffold design for tissue engineering

3. Filtration and Separation

- Porous membrane optimization

- High-efficiency filter design

Open Source and Reproducibility

All the code developed for this research is available and uses open-source tools:

# Main libraries used

import numpy as np

import porespy as ps

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy import ndimage

import heapq # For efficient A-Star implementation

# Example of porous medium generation

def generate_porous_medium(porosity, size=100, blobiness=0.5):

return ps.generators.blobs(

shape=[size, size],

porosity=porosity,

blobiness=blobiness

)Impact and Publication

This research culminated in a publication in Computation journal (MDPI), with impact factor and peer review. Seeing our work cited by other researchers and contributing to global scientific knowledge was an incredibly gratifying experience.

Paper Metrics:

- Journal: Computation (MDPI)

- DOI: 10.3390/computation10040059

- Type: Open Access

- Review: Peer-reviewed

Lessons for Future Researchers

For Computer Science Students

- Don’t limit yourselves to traditional applications: Algorithms can solve problems in physics, biology, chemistry, and more

- Collaborate interdisciplinarily: Some of the best innovations arise at the intersection of disciplines

- Document everything: Reproducibility is key in scientific research

For the Scientific Community

- A-Star is underestimated: While more modern algorithms exist, A-Star remains a powerful and versatile tool

- Cross-validation is essential: Comparing multiple methods strengthens confidence in results

- Synthetic data can be valuable: You don’t always need experimental data to do meaningful research

Looking to the Future

Possible Extensions

- 3D Porous Media: Expand the algorithm to handle three-dimensional structures

- More Advanced Algorithms: Explore contraction hierarchies or transit routes for greater efficiency

- Machine Learning: Use neural networks to predict tortuosity directly from images

Emerging Applications

- Battery Materials: Porous electrode optimization

- CO₂ Capture: Adsorbent material design

- Personalized Medicine: Analysis of porous tissues in medical images

The Personal Journey: From Code to Science

Looking back, this research experience was transformative. It taught me that computer science isn’t just about creating applications or systems; it’s about solving real human problems using computational tools. The excitement of seeing how a pathfinding algorithm could contribute to clean energy technology development was the moment that defined my career.

The challenges were real too. Understanding fluid dynamics concepts, learning about material characterization techniques, and translating between computational and physical domains required patience and persistence. But every breakthrough moment - when the correlations converged, when our validation matched theory, when we saw our algorithm outperforming traditional methods - made every challenge worthwhile.

The Interdisciplinary Mindset

This project taught me to think beyond the boundaries of my field. It showed me that the most impactful research often happens at the intersection of disciplines. Computer science provides powerful tools, but the problems worth solving often come from other fields - materials science, biology, environmental engineering, medicine.

Conclusion: When Passion Meets Purpose

This research showed me that computer science is not just about creating applications or systems; it’s about solving real human problems using computational tools. The excitement of seeing how a pathfinding algorithm could contribute to the development of clean energy technologies was the moment that defined my career.

For any student reading this: don’t be afraid to explore outside your comfort zone. The most interesting problems and most elegant solutions are often found at the intersection of seemingly unrelated disciplines.

The A-Star algorithm will continue finding paths, whether in video games, robotics, or porous materials. And that versatility is precisely what makes computational science beautiful.

The experience of applying computer science to materials engineering was both exhilarating and humbling. It reminded me that the algorithms we study in textbooks can have real impact on technologies that could help solve global challenges like clean energy and sustainable materials.

Interested in interdisciplinary research? Have you applied CS algorithms to other fields? I’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments.

References:

- Espinoza-Andaluz, M.; Pagalo, J.; Ávila, J.; Barzola-Monteses, J. An Alternative Methodology to Compute the Geometric Tortuosity in 2D Porous Media Using the A-Star Pathfinding Algorithm. Computation 2022, 10, 59.